A young Arizona Black Rattlesnake from the eastern end of their range, in Greenlee County, Arizona. With most of the light cross bars already having disappeared into the background color, this one may be an interesting looking adult.

A young Arizona Black Rattlesnake from the eastern end of their range, in Greenlee County, Arizona. With most of the light cross bars already having disappeared into the background color, this one may be an interesting looking adult.

This Arizona Black Rattlesnake noticed me at the same time that I saw it as I climbed up a steep, rocky hillside. I stopped and got a few photos, and saw another one right next to it deeper in the crevice of the rocks. I was able to then back down the hill for another route up without further disturbance, and it resumed its move out to the open to get some sun.

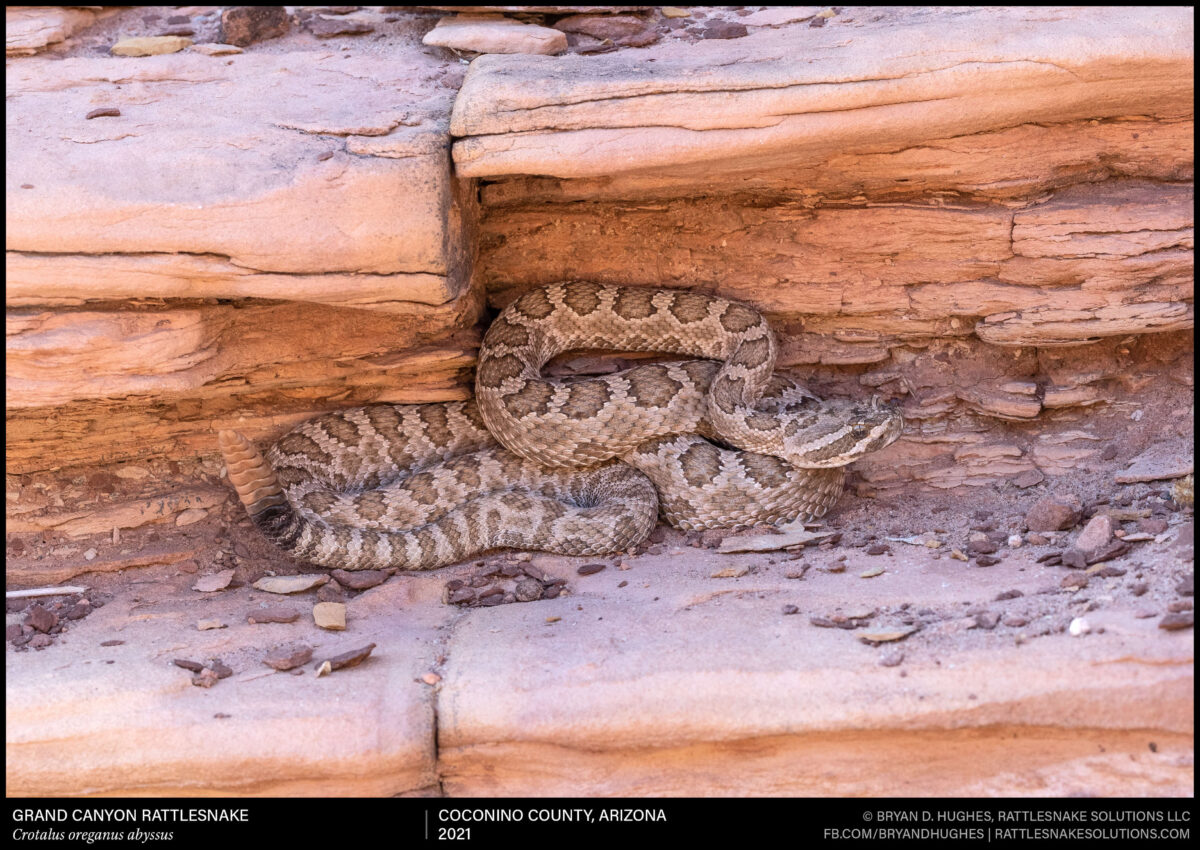

A Grand Canyon Rattlesnake from northern Arizona. In time, the pattern on this snake may continue to degrade and fade, but not to the same degree as is common for females of the species.

A Sonoran Desert Tortoise resting in the shade in on a hot morning in the Big Horn Mountains of western Arizona. These tortoises become nocturnal during the hottest parts of summer, moving and eating after dark and returning to their deep caves by the time the sun hits the area again.

A Mojave Rattlesnake from the Phoenix area. These snakes are common in the flatter, creosote and grassland areas of the state. This one obeys the all the ID rules, with much wider white tail bands than black, yellow proximal rattle segment, and a post-ocular stripe that extends back to never intersect with the mouth.

An Arizona Ridgenosed Rattlesnake we saw after dark in southeastern Arizona. These small snakes are great at hiding, and the locals rarely even know they exist.

Arizona Black Rattlesnakes are amazingly variable in appearance across their range. Most that are seen and photographed are in the relatively well-populated areas of the Mogollon Rim between Flagstaff, Prescott, and Payson. In other parts of their range, however, they look a bit less familiar. This one from the far eastern end of their range in largely inaccessible ranges of Greenlee County has a much messier, mottled look than is typically expected of the species, but common in the area.

A Blacktailed Rattlesnake hiding deep in a cave on an extremely hot day. During the heat of summer, rattlesnakes like this one may stay hidden away from lethal temperatures, staying in one spot or coming just outside the entrance after dark.

An Arizona Ridgenosed Rattlesnake in southeastern Arizona. These small rattlesnakes are common where they are found, but even ranchers born and raised in the area usually have no idea it exists. That’s thanks, in part, to its nearly perfect camouflage, making it about invisible in oak leaf litter and bunchgrass.

A Gila Monster peeking out of its spring staging spot, just down the hill from where it spent the winter. It shares this spot with several other Gila Monsters, a handful of Western Diamondback Rattlesnakes, and the occasional tortoise. It will spend the majority of each day during the early spring doing, basically, this. Resting in partial sun, disappearing if predators approach, and waiting to head out in nest-hunting mode as soon as the time is right.