A Twin Spotted Rattlesnake at her high elevation retreat. Accessing these areas is somewhere between difficult and impossible, but they’re perfect for a small montane rattlesnake.

A Twin Spotted Rattlesnake at her high elevation retreat. Accessing these areas is somewhere between difficult and impossible, but they’re perfect for a small montane rattlesnake.

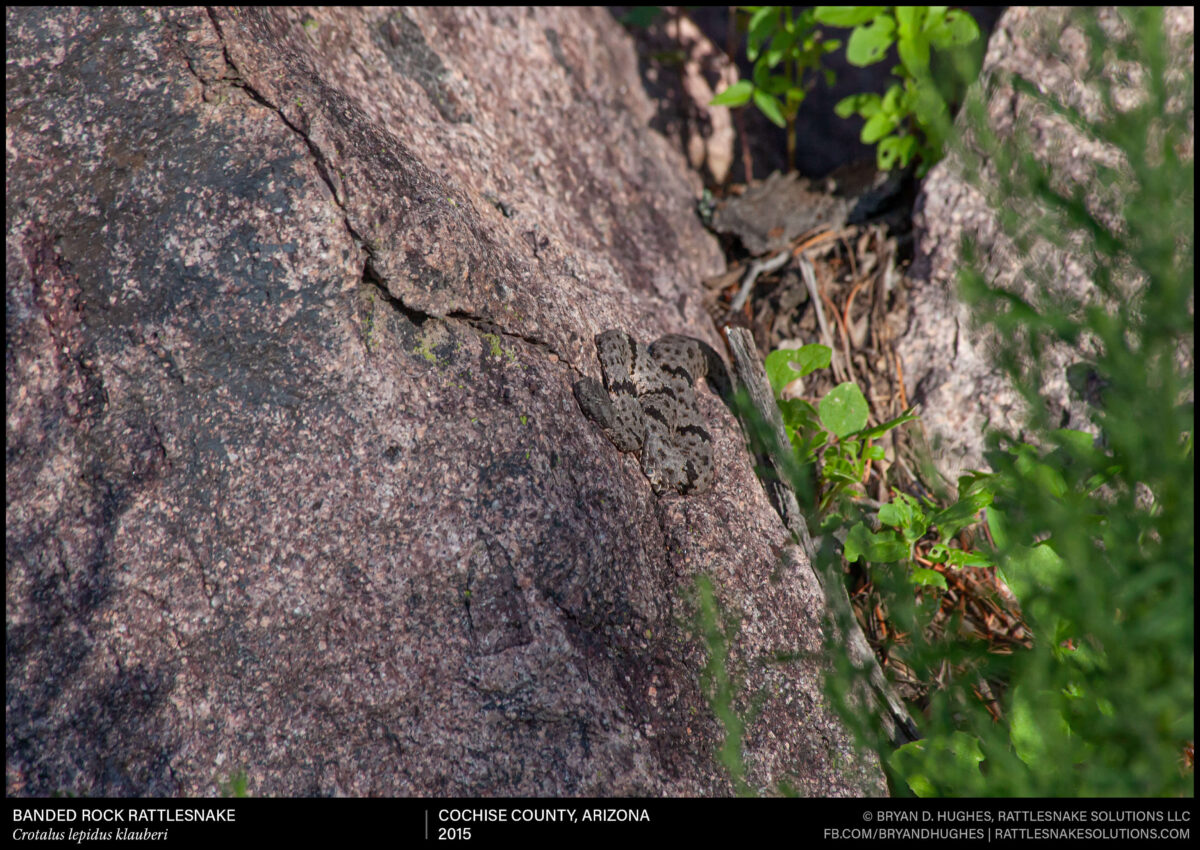

A small Banded Rock Rattlesnake in ambush along the base of a boulder in southeastern Arizona. The pattern and bands break up its shape, making it difficult to see in context. This is a good way to catch one of the many Yarrows Spiny Lizards jumping around on the same rocks each morning.

A Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake in ambush on a humid night a couple of years back. Like many other desert reptiles, the monsoon and period after are the most active times of year. Humid air and cooler, stable temperatures make for safer activity, and a lot has to be done in a relatively short amount of time.

Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake (Crotalus pyrrhus)

A Twin-Spotted Rattlesnake with a relatively drab pattern, but not atypical for an older adult. These are small snakes, rarely seen by hikers, as their range within the U.S. consists of only a handful of mountains in southeastern Arizona. In addition to rodents, these rattlesnakes also specialize in lizards, often taking the colorful Yarrows Spiny Lizards also common to rocky outcrops in high pine forests. These are among the protected species within Arizona, but a good number of them still end up being taken from the mountains each year to enter the European black market.

Prival, D. B., Goode, M. J., Swann, D. E., & Schwalbe, C. R. (2002). Natural history of a northern population of twin-spotted rattlesnakes, Crotalus pricei. Journal of Herpetology, 36(4), 598–607. https://doi.org/10.1670/0022-1511(2002)036[0598:NHOANP]2.0.CO;2

Prival, D. B., & Schroff, M. J. (2012). A 13-year study of a northern population of twin-spotted rattlesnakes (Crotalus pricei): Growth, reproduction, survival, and conservation. Herpetological Monographs, 26(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1655/HERPMONOGRAPHS-D-11-00002.1

Prival, D. B., Goode, M. J., Swann, D. E., & Schwalbe, C. R. (1999). A comparative study of hunted vs. unhunted populations of the twin-spotted rattlesnake. Unpublished report, University of Arizona. PDF link

Grabowsky, E. R., & Mackessy, S. P. (2019). Predator-prey interactions and venom composition in a high elevation lizard specialist, Crotalus pricei (Twin-spotted Rattlesnake). Toxicon, 170, 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.09.003

Grabowsky, E. (2018). Venom composition of little known mountain rattlesnakes and predator-prey interactions of Crotalus pricei pricei and its natural prey, Sceloporus jarrovii (Master’s thesis). University of Northern Colorado. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses/251/

Bezy, R. L. (2021). Biogeographic outliers in the Arizona herpetofauna. Sonoran Herpetologist, 34(2), 45–58. PDF

Pough, F. H. (1966). Ecological relationships of rattlesnakes in southeastern Arizona with notes on other species. Copeia, 1966(4), 649–658. https://doi.org/10.2307/1441401

Bezy, R. L., & Cole, C. J. (2014). Amphibians and reptiles of the Madrean Archipelago of Arizona and New Mexico. American Museum Novitates, 2014(3810), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1206/3810.1

Kauffeld, C. F. (1943). Field notes on some Arizona reptiles and amphibians. The American Midland Naturalist, 29(2), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.2307/2420795

Gloyd, H. K. (1937). A herpetological consideration of faunal areas in southern Arizona. Bulletin of the Chicago Academy of Sciences, 5(6), 79–136.

A Madrean Mountain Kingsnake from the southeastern corner of the state. These colorful snakes can be surprisingly difficult to spot, despite their bright coloration. In the low, dappled light and noisy background of their woodland environment, there’s not a “snake shape” to see, and they’re easy to walk right by.

A Chihuahuan Hooknosed Snake we found in Cochise County, Arizona. These small snakes have a specialized scale on its face that it can use to help it uncover its prey: arachnids and centipedes. Of the snakes that can be found in Arizona, this is one of the least often seen, even by snake enthusiasts.

This one became defensive as it was being photographed, striking repeatedly at the camera with a closed mouth. This is a good example of why the popular saying “if it has a mouth, it can bite” is missing a critical component to be relevant: not just can it bite, but WILL it bite. This little snake says no.

A Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake from Yavapai County, Arizona, photographed earlier in the year. The combination of geology and lichen in the area produce some beautiful color combinations in the animals evolved to cryptically match it.

A Chuckwalla surveys its vast domain, just north of the Grand Canyon. Here, these large herbivorous lizards take on a sandy, mottled color, making them harder to spot against the ground by predators flying overhead. For an observer at ground level, however, the shape of a vigilant lizards popping up from outcrops and boulders is much easier to spot.

Blacktailed Rattlesnakes can live in a wide variety of habitats, from high pine forests to low desert around sea level. This one was found in Greenlee County, Arizona several years ago.

An Arizona Black Rattlesnake comes out of its den for the day on a warm Spring day. This site is shared by three species of rattlesnakes, and at least a few species of other snakes. As spring egress progresses, each will use the area slightly differently, emerging, staging, and eventually distributing on their own schedules.