Spring is here, and the annual Mojave Misinformation migration has begun. BS stories and local lore travel from the deserts of California though the Sonoran desert, stopping along the way to feed on the excitable click-bait of local news networks. Eventually this misinformation ends up in Eastern New Mexico, where brand new misinformation is born in places where this species doesn’t even exist. If you watch carefully, you can catch a glimpse of these “facts” as they pass through social media pages and community groups. The herd leaves its droppings along the way in massive amounts; be careful not to step in piles of “them is good eatin” or “need a new hatband” if you are in the outdoors.

The dreaded “mojave green” rattlesnake: monster of the desert …

Mojave rattlesnakes, or “mojave green” rattlesnakes, tend to get the most misinformation out of any species. This is speculation, but from what I have seen with the stories that form around other species, this is a case of personal communication. That is, this snake has a reputation for being overly aggressive and “nasty”, and is therefore a better conduit for people that would like to tell the world something about themselves. That could be a way to tell others that they are brave or adventurous, after tales of confrontations with the mojave monster and their fight to survive the attack, or just how much it doesn’t bother them to come into contact with such a menace on a regular basis. These individuals may also have stories of catching a record-sized fish that slipped away before anyone could get a photo, and has certainly been stalked by numerous mountain lions … and possibly bigfoot.

But of course, the real damage caused by intentional creation and spread of misinformation is that it can alter the context, though which people may perceive an encounter with a mojave rattlesnake, and how they remember it. A cloud of misinformation can distort that perception, and a person with an artificially increased sense of fear can actually remember things that didn’t happen, or remember them very differently. This distortion effect is well documented. That means that if a person spends years hearing and reading stories that are exaggerated in nature, it can change how they actually see a snake when it happens, and change the memory as well.

In this way, this sort of misinformation that transcends to local lore can create a cultural fear, where being scared of rattlesnakes is not only expected as a “common sense” mentality, and is even a point of local pride. Becoming educated on the matter becomes more difficult in these conditions, as the barriers are also social. I have experienced, personally, throughout my years of speaking in public about the reality of rattlesnakes, how this social barrier challenges education. When I am confronted with a story told about a 15′ Mojave Rattlesnake biting through a tractor tire, I cannot easily correct that statement with facts without accusing that person’s grandfather of being a liar.

Here are a few of the “facts” that regularly circulate on social media

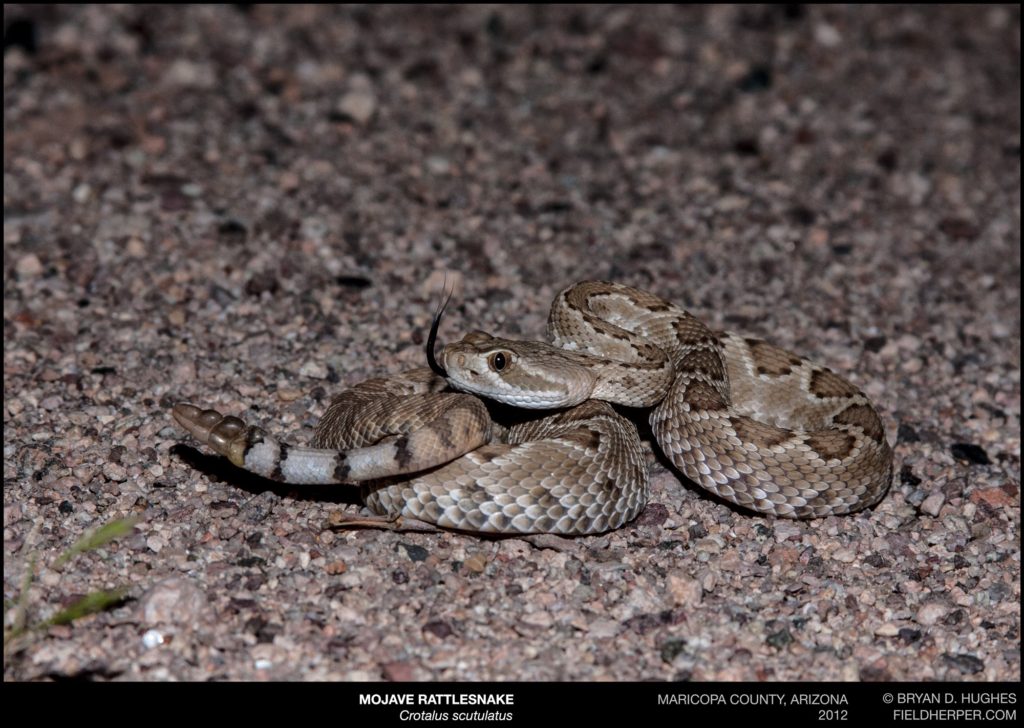

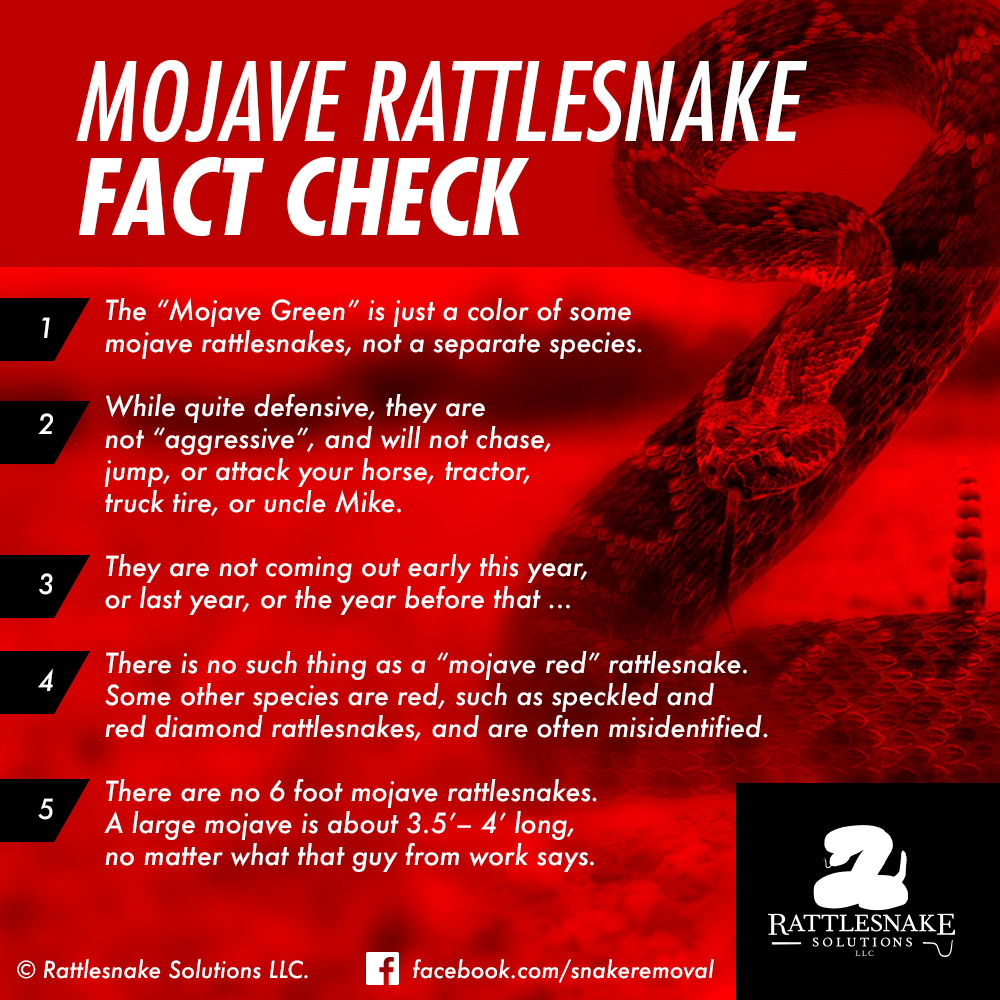

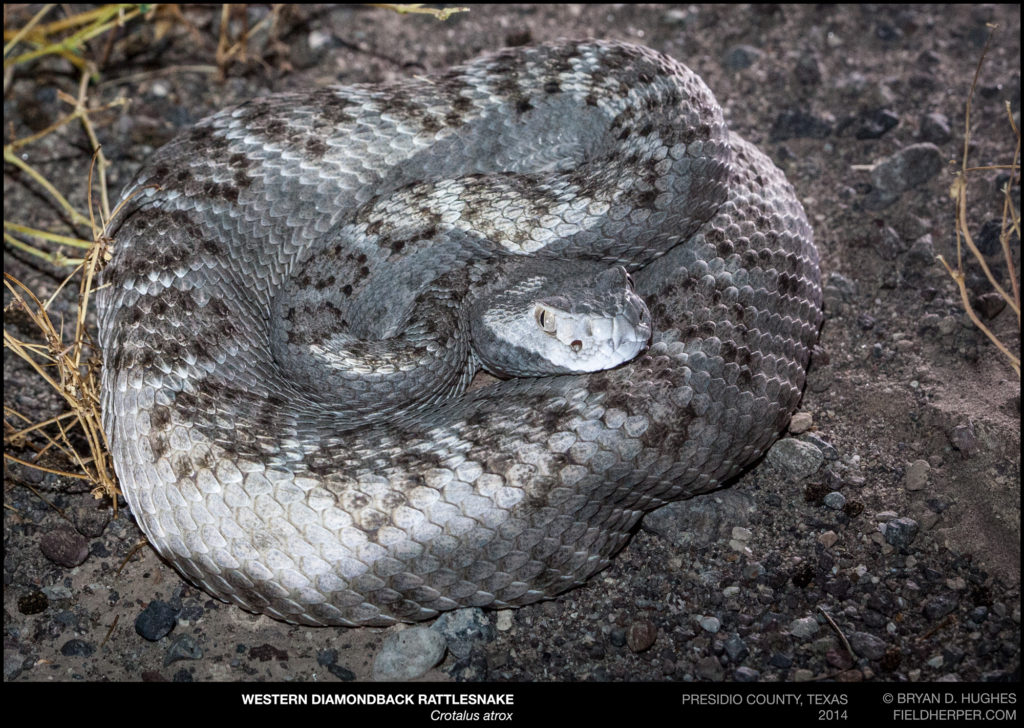

- The “Mojave green” rattlesnake is a not a hyper-aggressive, separate species of rattlesnake. Mojave Rattlesnakes can certainly be green, and even the brown ones look kind of green compared to the dull grey of their Western Diamondback counterparts. However, this can lead to confusion, where people misidentify any rattlesnake they see with a green coloration as a Mojave. A good example are the Blacktailed Rattlesnakes, found in mountains and regions where Mojaves either do not range, or do not use. Another are the reports of Mojave green rattlesnakes being found in parts of Eastern New Mexico where they do not live. When asked for photographs of them, I am emailed pictures of killed Prairie Rattlesnakes, with also look green. The reality is that, while Mojave Rattlesnakes are often green, the color green is not a good indicator for accurate identification.

- Mojave Rattlesnakes are not aggressive. This one is a semantic issue, for the most part. An aggressive animal is one that prompts a fight … it comes after you, throws the first punch, initiates the interaction. Mojave Rattlesnakes are, in reality, very defensive. This may mean that they can rattle and strike with more enthusiasm than other types of rattlesnakes, but this is a defensive behavior. That is, it’s started by you. Even accidental acts like stepping on a rattlesnake, though an accident, are initiated by the foot doing the stepping. After that interaction has begun, a Mojave Rattlesnake may, as part of its defensive behavior, even advance towards a person, either to get away or defend itself from its perceived attacker. Perception, as well, can be distorted by fear. Our minds do not always tell us the truth, in favor of escape from a perceived dangerous situation. (Rachman S, Cuk M Behav Res Ther. 1992 Nov;30(6):583-9) Mojave Rattlesnakes, in my experience with them, are definitely more touchy as a whole, but nothing that will take aggressive action. In fact, if rattlesnakes of any species were truly aggressive, and engaged in intentional attacks on people walking by, none of us would ever survive a hike in the desert.

- Mojave rattlesnakes are not coming out earlier this year. This is a story that local news throughout their range, and even in places where they aren’t found, like to run every single year. Rattlesnakes of all species are coming out right on time this year, as they have every other year this particular bit of misinformation has surfaced.

- There is no such thing as a “mojave red” rattlesnake. The desire to use the term “mojave” can be so strong, that it’s oddly made its way to other rattlesnake species as local common names. “What is this rattlesnake that isn’t green and isn’t a diamondback? Well, I won’t impress anyone with saying I don’t know … so it must be a mojave … red!”. The most common rattlesnake to get the name are actually Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnakes, who appear red or pink in much of their range. However, I have also seen instances of Red Diamond Rattlesnakes, Panamint Rattlesnakes, and Western Diamondback Rattlesnakes get the “mojave red” treatment. In reality a mojave is a mojave is a mojave, red, green, or otherwise.

- Mojave Rattlesnakes aren’t as big as many people claim. The largest confirmed Mojave Rattlesnake ever recorded is 48″ long, or 4 feet long (Schuett, Feldner, Smith, Reiserer, Rattlesnakes of Arizona, pg 568). Reality is that people just aren’t great at estimating size, especially at distance, from memory, or of an animal that causes anxiety or fear. Claims of a rattlesnake measuring a full third or more of the largest individual ever documented are common, which begs the question: why are the snakes researchers, scientists, students, or any of the many, many thousands of individuals that are documented so small? Weighing the entirety of both scientific documentation and anecdotal evidence by informed individuals with reports by a populace that loves to distort facts regarding rattlesnakes: there isn’t much of a question what is happening here. Mojave Rattlesnakes are a medium-sized snake, and an adult is usually in the 3′ range. My apologies to your uncle with the stories; it didn’t happen.

This post could go on and on, and perhaps it should. There are many, many more myths about this animal than this group, but this post and associated graphic may address the majority of posts I see on social media about these misunderstood snakes. Really, Mojave Rattlesnakes are not so bad. Viewed in context of wide-spread misalignment on reality, cultural pride in our “dangerous” animals, they are very scary indeed. The next time someone claims that an 8′ mojave rattler done chased their horse for a half a mile, remind them that you know better, and most other people do too.